Becoming financially literate is crucial for HR professionals who want to make a greater impact and foster better partnerships with the finance function and the business overall.

Use this article as a starting point to learn the terminology, metrics, and decision criteria necessary to get your next project funded.

The Case For Better HR Financial Literacy

For many HR professionals, it’s frustrating to see the amount of emphasis and effort leaders place on the finance function.

This is especially true when there are pressing issues concerning talent management that need to be addressed.

So the question becomes, how can HR convince the business to address challenges in the workforce?

Even a basic level of financial literacy will help HR professionals to:

- Capture the attention of influential decision-makers who can help you fund HR projects.

- Enhance the impact HR can have on the overall business objectives and strategy.

- Display financial competency to leaders who can support/advance your career.

Reality Check

In our current economy, organizations are specifically designed to make money, and the ones that prevail are focused on making more than they spend.

Executives are tied to, and incentivized by, the fiduciary responsibility of generating revenue and limiting costs (to the extent of their mission, values, and culture).

This is why so much effort is put into managing the finances of the business. The executives' jobs are on the line, and the investors want to know how their investment is progressing.

But the age-old question remains, aren’t people the most important part of any business?

Well, yes and no.

Yes, because people do the work. No, because organizations are graded and valued on how well they manage their money.

If HR is to secure a larger portion of the available funds, it needs to align with how executives manage the business, articulating impact through financial leverage.

This means HR professionals must understand, interpret, and influence executives on how HR’s initiatives affect the business financially.

To do so, many of us still need a little help with the terminology, metrics, and decision criteria used to allocate resources.

It’s not that you need a full course in accounting or financial analysis, but develop a level of competency to communicate in the black-and-red language of finance.

Key Financial Terminology

Overall, managing a business is relatively straightforward if you consider the main components.

There’s revenue from selling a product or service and costs or expenses associated with operating the business. The difference between the two is the profit.

A business measures its profit in two ways: the aggregate amount of dollars generated or the ratio of those dollars to sales, i.e. margin. Of the two, it’s easiest to compare using a margin.

To fully grasp the margin concept, I recommend diving in deep enough to understand the differences between the three types: gross profit, net profit, and operating profit.

Each offers a perspective into how efficiently a company is operating. Additionally, there are varying ranges specific to your organization’s industry or sector that indicate if the margin is good or bad.

Every business wants to increase its profit, whether that’s from:

- Sustaining revenue and decreasing costs,

- Growing revenue and keeping costs linear to that growth, or

- Growing revenue and decreasing costs—this is obviously ideal!

In either case, the remaining profit then gets allocated: some goes to the owners/shareholders and the rest typically gets reinvested back into the business. For consistency throughout this article, we’re going to assume some level of profit is realized.

The total funding pool, or cash, consists of the reinvested profits plus whatever balance is left from the prior year’s annual budget, which is readjusted each fiscal year. Leaders then have discretion on where to allocate those funds.

Note: If the business is doing well enough, there’s usually available cash, a slush fund if you will, for special projects beyond what’s typically budgeted. While tough to secure, executives will use these discretionary funds if the business case supports one of their key objectives.

Funds For A Purpose

For every dollar that is allocated, executives are expecting to see a return on investment (ROI), or impact in the form of process improvements, higher revenue/sales, lower costs, innovation, etc.

Knowing this, you can imagine how important it is that every project, initiative, or new technology should produce a gain for the business.

So this next step is imperative.

Many HR projects are pitched as an expense, not an investment. Herein lies the problem.

Due to their incentives and responsibilities, executives want to see what the impact or return will be i.e. increased revenue or lower costs. There are other intangible benefits or returns, but here I’m focusing on the main economic drivers.

To reposition a project from an expense to an investment requires a bit more work.

But, like anything else, it takes a little practice and often a willing colleague’s help (more on that below). That work comes in the form of financial metrics that serve as decision criteria. I list a few common ones in the next section.

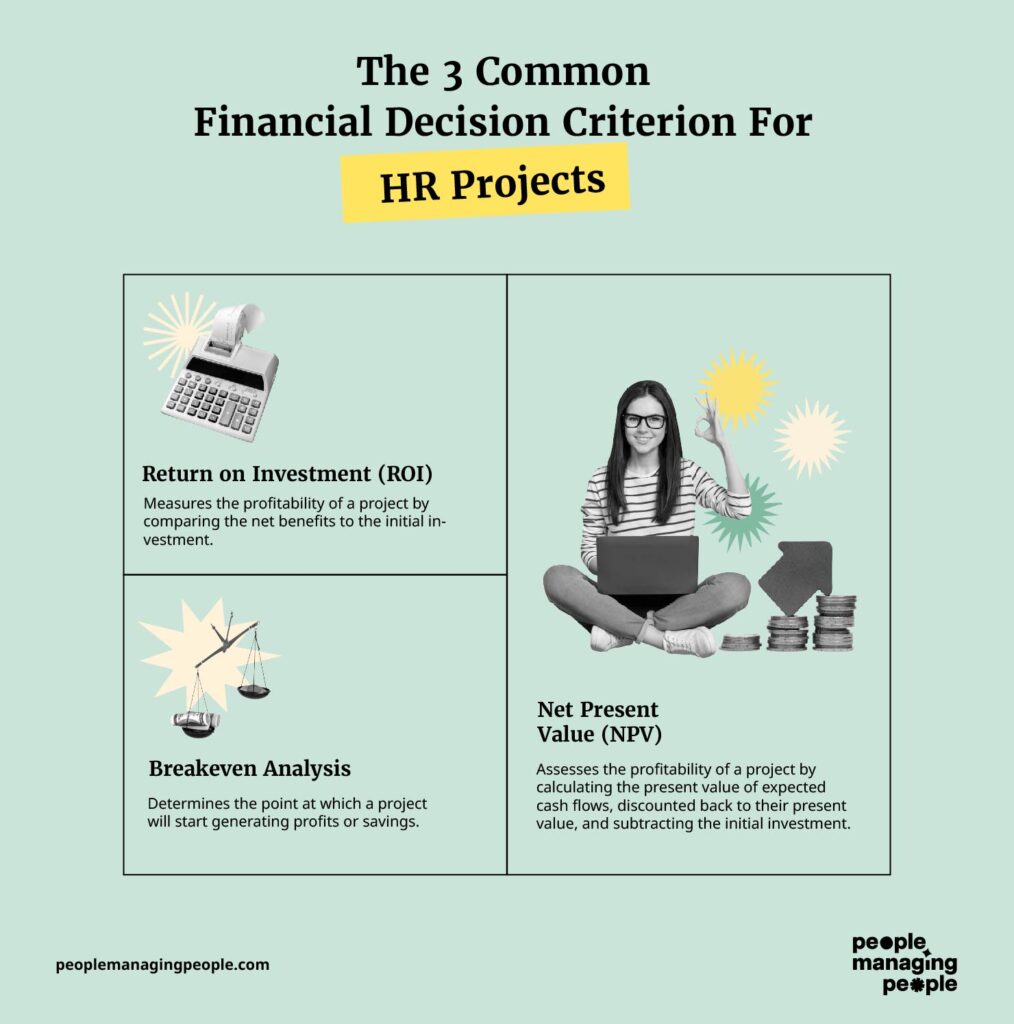

3 Common Financial Decision Criterion For HR Projects

Please make a graphic for here using the following copy:

Return on Investment (ROI): Measures the profitability of a project by comparing the net benefits to the initial investment.

Breakeven Analysis: Determines the point at which a project will start generating profits or savings.

Net Present Value (NPV): Assesses the profitability of a project by calculating the present value of expected cash flows, discounting back to their present value, and subtracting the initial investment.

1. Return on Investment (ROI)

Measures the profitability of a project by comparing the net benefits to the initial investment.

Example: A sales training course

If it costs $10k to train salespeople, the business will expect sales to increase by at least $10k within a reasonable period.

Benefits: ROI provides a clear percentage that helps compare the profitability of different projects.

Limitations: In its most basic form, it doesn't account for the time value of money or risks associated with the project.

Best practices: If your ROI is calculated to be above a 20% return, your assumptions are too generous or you should switch to a breakeven analysis.

2. Breakeven analysis

A break-even analysis determines the point at which a project will start generating profits or savings. This is where total revenues (or cost savings) equals total costs, and the project neither makes a profit nor incurs a loss.

Example: Implementing a new recruiting system

A new recruiting system is expected to process candidates faster, reduce time to administer, and provide added functionality to accelerate hiring processes.

The savings in efficiency or effectiveness should outweigh the overall system costs at a certain point in time as compared to the existing system.

Benefits: Helps in understanding the minimum performance required to avoid losses.

Limitations: Assumes costs and revenues are linear and don’t account for the time value of money.

Best practices: In most cases, your breakeven should be within 18 months. If not, most Finance professionals will consider this analysis invalid. Breakevens should be shorter—try using NPV.

3. Net present value (NPV)

This assesses the profitability of a project by calculating the present value of expected cash flows, discounted back to their present value, and subtracting the initial investment.

While this is a common evaluation, it requires advanced knowledge. I included it as an option for those willing to make the effort.

Benefits: Takes into account the time value of money and provides a dollar amount that shows the project's contribution to wealth.

Limitations: Requires accurate estimation of future cash flows and an appropriate discount rate.

Best practices: Work with a Finance colleague to ensure you have the correct assumptions, rates, etc that fit your organization’s typical parameters.

There are other metrics like Internal Rate of Return, Payback Period, and Profitability Index that are useful too.

However, it’s most important to ask your leadership how projects are being evaluated both within HR and cross-functionally.

Competing For Resources, Not Just A Budget

This goes back to one of my initial points. Resources (time, money, and people) are allocated according to how projects will impact the business. The bigger the impact, the more attention a project gets.

For every executive decision, there are trade-offs and opportunity costs.

Weighing these options means carefully evaluating how the resources will be used to generate the estimated impact. To easily compare projects and costs, the above metrics serve as standardized criteria to assist in decision-making.

Having a comparable set of metrics helps to clearly evaluate projects between functions as well as estimate future budgeting and forecasting efforts.

Because HR typically has one of the smallest budgets, we need to shift our thinking. Too often we don’t even pitch projects because we’re told it isn't in the budget. But what if we tossed those apprehensions to the side and instead asked for more money or sought funds from other pools of capital?

For a high-potential project, it’s worth the effort to pitch a proposed reallocation and, if you can show your project’s metrics outweigh another, then allow someone at the appropriate pay-grade to make the final call.

However, it’s sometimes tough to know what you’re up against.

Depending on your visibility, knowing what other projects are being considered, and even their timing, can be challenging.

This is why it’s important to cultivate relationships with other functions, especially Finance.

Garnering Cooperation: Your Network Is Your Net Worth

Awareness of the businesses’ priority projects, available funding, and decision criteria provides you an advantage on how to best position your projects.

Oftentimes the finance or operational functions have this knowledge.

Start by building a cross-functional network with people you trust and are at a similar level. Base the relationship on being interested in their work and simply learning how their role plays a part.

Frankly, this is a good general practice for any HR professional to know your workforce’s skill sets.

Further, try to understand what motivates them in terms of career goals or growth. Concentrate on providing a perspective through HR’s lens they might not consider or share how to access HR resources that can advance their career.

In return, work with them to link your project’s impact to some of the decision criteria and metrics mentioned above. I’d ask them how they would tie the results back to top-line revenue or bottom-line cost savings. Getting their stamp of approval could be helpful.

However, be careful with whom and how you connect, and don’t share confidential information under any circumstances.

The more you understand where the business is investing its resources, the better you can position your projects to compete. Sometimes it takes a village, to get to know the other villagers.

Literacy, Networking, and Storytelling

HR professionals are burdened with a daunting task. We’re asked to balance the needs of the workforce, be a talent advocate, and serve the objectives of the organization.

To continue to advance the value HR delivers, we must retain enough financial literacy to competently compete for the resources we need.

This requires us to adapt to the financial-driven decisions executes must make every day. To navigate this landscape, it’s imperative we integrate the financial acumen needed to articulate our unique propositions.

Effectively communicating the financial impact of HR initiatives can significantly increase the likelihood of securing necessary resources and support from executives.

By mastering key financial metrics, cultivating a broad network, and crafting compelling stories, HR can transform projects from perceived expenses into valuable investments.

Useful Resources

Below are a few books that I’ve found useful throughout my career:

- Orloff, J. & Mullis, D. (2008). The Accounting Game: Basic accounting fresh from the lemonade stand. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks. IBN- 13: 978-1402211867 (e-book is less effective.).

- Seeing the big picture: Business acumen to build your credibility, Career, and Company. (Mullis)

- Berman, K. and Knight, J. (2013). Financial Intelligence, Revised Edition: A manager's guide to knowing what the numbers really mean. Boston: Harvard Business Press.