“How was your man meeting?” my HR manager asked me, raising her eyebrows as she hurried past the flow of people leaving the glass-panelled meeting room where we’d had our weekly management meeting.

She made her point quite clear. With only two women on the team of 14 that I’d inherited when I became Joint Managing Director of a London-based marketing agency, it was obvious that there was a disconnect between the rhetoric and reality of our claims to be a diverse and inclusive workplace. And, in my first year in the role, I’d done little to shift this.

I was grateful that she felt enough psychological safety with me to point this out. That’s something we’d focused on instilling into our culture in my first year in the role.

I’d share my performance review openly with my team. Our Directors’ development areas were posted publically to ensure people could hold us to account and see we were working on things too.

We’d co-created a set of corporate values with our team rather than dictating them from the top.

My Co-Managing Director (another white male) was open about attending therapy and took extended parental leave to role model the importance of men doing this as well as women.

But we hadn’t really got to what we, at the time, viewed as the ‘hard stuff’: representation at the senior leadership level and ensuring that our business really was an inclusive place to work.

Another conversation several weeks later impacted me in a similar way. As a straight, white man in a position of power, keen to understand the experience of people in our agency who didn’t look like me, I’d gone to lunch with one of our senior consultants, an Indian woman who had previously expressed concerns about us not walking the talk.

I trusted she wouldn’t sugarcoat her experiences for me and she didn’t! She brought to life her experience of being an Indian woman with an accent working in a predominantly white space.

She also gently reminded me that I could not rely on her (or other team members who identified differently from me) to educate me about their lived experiences. If I was serious about being an inclusive leader, I needed to do the work myself and recognize the burden I would be placing on others by asking them to educate me.

She recommended that I read ‘White Like Me’ by Tim Wise. I did, and it marked the start of my ongoing education to appreciate my own whiteness, privilege, and how I contribute to systems that work in my favour and against others who don’t look like me.

Within a couple of weeks of these two conversations, we’d reviewed our management structure and made some immediate changes to the team. Over time, this had evolved into a group of the most senior client Directors in the agency, many of whom did not head up teams or departments.

We asked three men to leave the management team to focus on their clients. Three women who were heading up large teams were invited to join the group. It was an important moment for us, signalling to people that we were intent on driving change.

We were moving in the right direction, but I was acutely aware that all the faces in the room except one were white, like me. We still had such a long way to go. It was humbling to realize how far I was from being a truly inclusive leader.

Apparently, I’m not alone in this regard. Recent research shows that 66% of leaders over-estimate their inclusion efforts and only 31% of employees think their leaders are ineffective at creating an inclusive team environment.

Well-meaning platitudes advise leaders to ‘do the work’, ‘have the difficult conversations’, ‘start with themselves’, and ‘understand that it’s a lifelong journey’. The advice is valid, but it doesn’t necessarily help someone know where to start, or how they can improve.

In my experience, learning to lead inclusively starts with understanding what good looks like.

I’ve appreciated efforts in recent years to better define what strong inclusive leadership looks like, and the development of thoughtful frameworks which codify specific behaviours which contribute to inclusive leadership.

In this article, I share several frameworks which I hope will inspire you to think about how you’re showing up as a leader.

My hope is that you take a moment to read them and reflect on where you might improve, use them as a stimulus in development conversations (your own and your team's), and set goals that build your capabilities in this critical leadership competency.

What does it mean to be an inclusive leader?

Definitions of what it means to be an inclusive leader have shifted over recent years, but the topic of inclusive leadership continues to headline leadership conferences.

Looking back on my early years as a Managing Director, I recognize my own efforts to be an ‘inclusive leader’ in definitions which speak to ‘valuing contributions from team members’, ‘striving to create an atmosphere where people feel their opinions matter’, and ‘prioritizing collaboration and open communication to make decisions and solve business problems’.

People courageous and caring enough to point out my biases and knowledge gaps helped me to understand that true inclusive leadership is necessarily more activist and urgent.

Shakenna Williams, Executive Director at Babson’s Center for Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership (CWEL), points out that inclusive leaders need to lead without bias. They ‘authentically commit to diversity, inclusion, and equity. They seek to understand other cultures, challenge the status quo, and be an advocate of equity for all.’

With this in mind, here are three frameworks that you can use to develop into a more inclusive leader.

Practical Framework 1: The six Cs of inclusive leadership

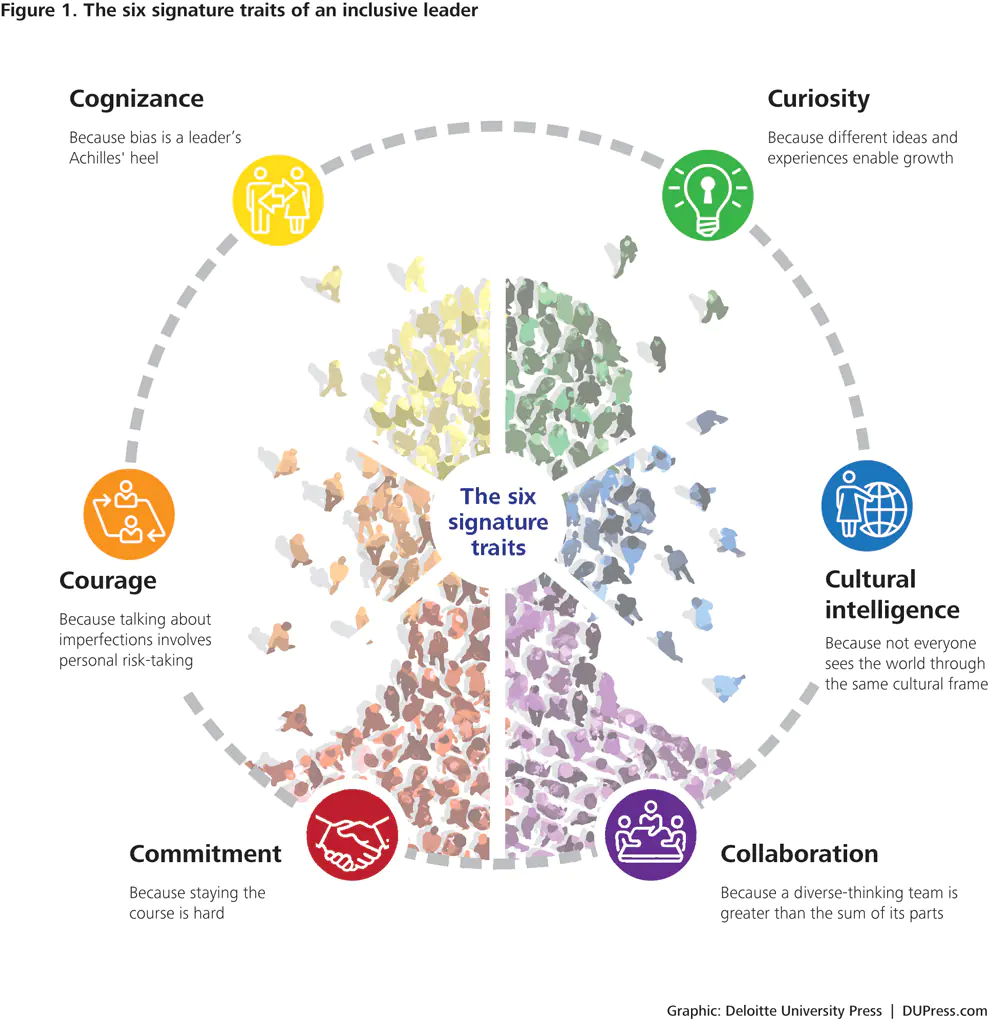

Back in 2016 (a year after I took on my role as Managing Director), Deloitte pointed to the increasing diversification of markets, customers, ideas, and talent as critical reasons why leaders must build capability around inclusive leadership.

They detail six signature traits of inclusive leadership, pointing out that leaders who model these behaviours do so primarily because these objectives align with their personal values, and secondarily because they believe in the business case for building more inclusive businesses.

The model is helpful in the way it breaks each trait down into specific elements, linking them to behaviours that leaders should exhibit to others.

For example, ‘courage’ is broken down into having the ‘humility’ to recognize personal gaps in knowledge and having the ‘bravery’ to ‘speak about their own limitations in a very personal way’.

As I reflect on what I’ve got right and wrong over the last few years, I realize that this is what I am in part trying to do by writing this article.

While discussing my own journey, I fear some may view my reflections as ‘self-congratulatory’. My hope (and ultimately my conviction) is that by being open about what I have learned, and the mistakes I have made and continue to make, I may create permission or act as a catalyst for others to do the same.

Practical Framework 2: A strength-based approach to inclusive leadership

I recently came across another excellent framework that can be used by leaders seeking to become more inclusive in their approach.

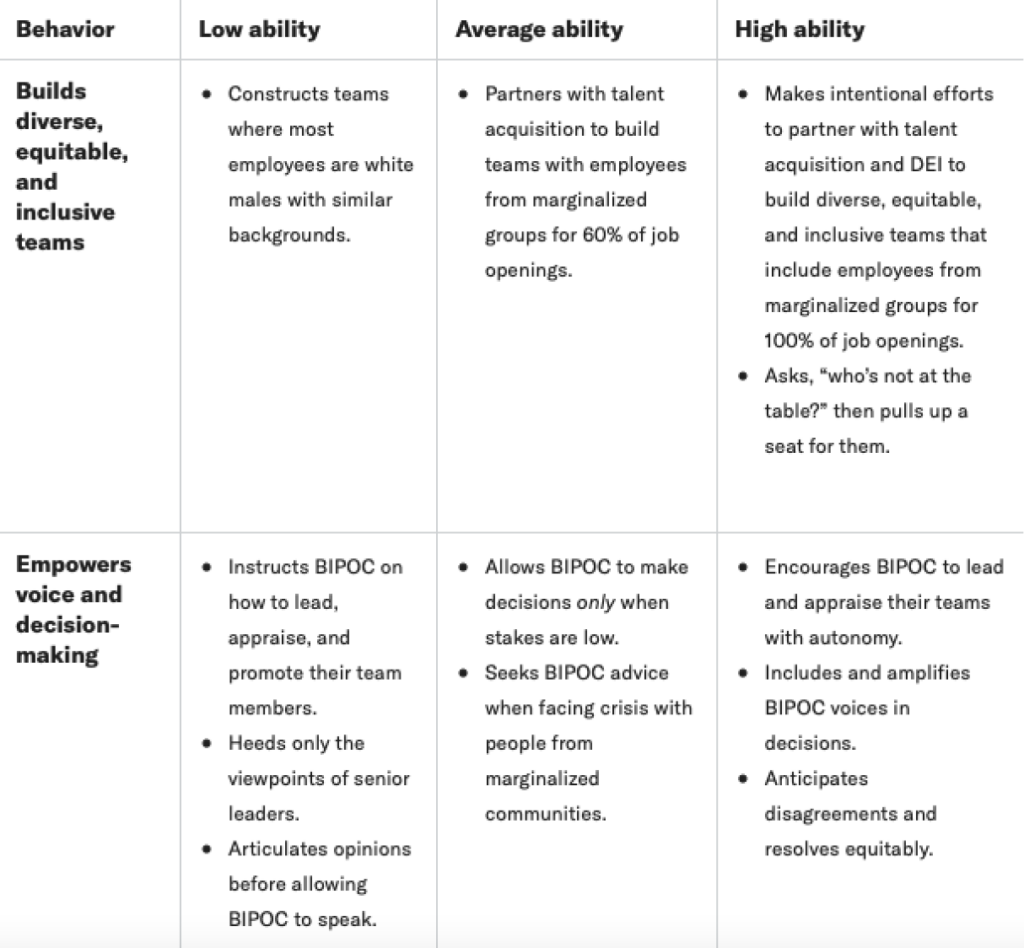

Salwa Rahim-Dillard offers a strength-based approach where people can identify their behavioural strengths in order to create a roadmap to becoming a more inclusive leader, focusing particularly on relationships with BIPOC employees.

I find this model particularly helpful in the way that it crystalizes very specific behaviours of inclusive leadership so leaders can benchmark their abilities (as low, average or high) for each behaviour and set goals for improvement.

After my time as Joint MD, I moved into a bigger role as global Chief People Officer.

Seeking to bake inclusive behaviours into our business culture and systems, we rewrote our company competency framework to clarify what inclusive leadership behaviours we expected people to demonstrate as they progressed through the company.

We did an admirable job co-creating this with our team, but, in hindsight, I wish we’d also had these frameworks to hand.

They’re rich with examples of what inclusive behaviour does and doesn’t look like, and I know they would have led to some deep personal reflection, thought-provoking conversations and action planning.

Practical ‘Framework’ 3: A phrase to guide in-the-moment decisions

While the above frameworks can be incredibly helpful, I find them less useful in helping me know how to act ‘in the moment’.

I believe that inclusive leadership isn’t always about thoughtful planning. It’s about how you show up each day, in moments under pressure, when you mess up, when the heat is on…

In these moments, when I’m feeling overwhelmed or unsure of how to act or what to do, I find myself returning again and again to a phrase I stumbled on a few years ago:

‘You have to think about when to stand up for someone, when to stand beside them and when to stand behind them.’

Standing up for someone…

There are times (as a result of the power, position, and privilege that comes with being a leader or identifying in certain way (e.g. as a white man) that you may find yourself in a situation or space where you need to speak on the behalf of a person or group who is not present.

You may have access and influence over spaces, people, or resources that they do not have. Your privilege or position may afford you the safety to speak out in a way that they can not.

Of course, it’s important to do this in a way that does not further marginalize a group or individual by making assumptions about their (life) experience or preferences.

What this might look like…

- Recognize where bias may exist and call it out: ‘Before we start developing this website, have we thought about how accessible it will be to people with disabilities?’ or ‘I don’t think we should mandate that everyone has their video on through every call. That can be exhausting for neurodivergent people’.

- Bring others’ voices into the room: ‘This is really important to our LGBTQ+ team members’ or ‘I don’t think we have enough experience of this to make this decision. We need to talk to our female engineers to get their POV first.’

- Advocate for others who aren’t there: ‘We should send this job opportunity to Kate while she’s on maternity leave.’ or ‘Ryan would be a better fit for this speaking opportunity than I would. He actually has lived experience of the topic.’

Standing up for someone also means leading from the front. This will also include:

- Using your power and privilege to address systemic issues that impact inclusion and belonging where you work (e.g. pay equity analyses, addressing bias in hiring processes, educating leaders and managers around bias, providing resources and safe spaces for historically-marginalized groups, etc.).

- Role modelling the behaviours detailed in the frameworks discussed earlier.

Standing beside someone…

At a fundamental level, I see this as accepting that you can never truly understand someone else’s life experience, but that you can listen hard to understand differences and work with people to drive positive change.

What this might look like…

- Listen hard to the people that you work with and act on their feedback. Are your policies and communications using gender-inclusive language? Do people have safe spaces where they can provide honest feedback? Are you celebrating diverse cultural events and holidays? A simple shift for us was enabling people to swap out federal public holidays for dates that were religiously or culturally significant to them.

- Doing the work to educate yourself about others’ lived experiences. Listen to podcasts and diversify your social media feeds by following people who don’t look like you. Read books—non-fiction and fiction. A few that have really impacted me over the years: How to be Less Stupid About Race (Crystal M. Fleming), Don’t Fix Women (Joy Burnford), Minor Feelings (Cathy Park Hong), Me and White Supremacy (Layla F. Saad), Divergent Mind (Jenara Nerenberg).

- Educate people in your organization about what inclusive leadership looks like. The burden to do this shouldn’t sit on the shoulders of those with less power or privilege.

Standing behind someone…

Perhaps most challenging for me was recognizing when my role as a leader was not to speak for someone, to ‘rescue’ or ‘save’ them, but simply to remain quiet and get out of their way.

What this might look like…

Recognize when you need to stop talking

In meetings, invite quieter voices into the conversation by asking people what they think if they haven’t contributed yet.

Don’t defend or explain yourself when someone gives you feedback about something you could do to be more inclusive. Say thank you and listen.

I’ll own that I don’t always get this right, but increasingly, I now try to call myself out before someone else needs to - “Sorry, I think I just interrupted you just then. Let me be quiet so you can speak” or “Ugh, I think I just mansplained to you how to do your job. Let me shut up so you can get on with it.”

Create a platform for others to shine

You don’t always need to be the person who announces the new policy, gives the presentation, or makes the pitch to the leadership team. Work behind the scenes with people and find opportunities for them to take the spotlight.

I remember when we conducted a candid deep dive into what our employees thought of our approach to diversity and inclusion.

As Chief People Officer, I was itching to take the stage and share the findings back with the company… and it would have been entirely inappropriate for me to do so.

But, by me getting out of the way, the team delivering it back was able to tell a more compelling and authentic story than I ever could have.

Provide time and resources for employee-led inclusion initiatives

Many of the people in your organization who are working hard on projects to make your business inclusive won’t be getting paid to do this extra work.

It typically comes on top of their day jobs. We didn’t fully crack this, but started to make progress in ensuring people who contributed to this agenda were rewarded for it.

Inspired by what we’d heard about at LinkedIn, we built a case for leaders of our identity-based Employee Resource Groups to receive a financial bonus.

We started to carve out small budgets for these groups to coordinate activities that educated the rest of the business about their lived experiences, or to spend on fostering connection within the group they were part of. This didn’t all happen at once, but built over time as we listened hard to how people in these groups were feeling.

A continuous journey

Becoming an inclusive leader isn’t a destination you arrive at one day, or a title you earn, like a promotion. It’s an active, intentional, ongoing process. Whether you are viewed as one isn’t for you to decide. It will be decided each day by each of the people you’re working with.

None of us gets it right all of the time, and as the world, our organizations, and the people we work with evolve, so must our approach to leading inclusively. To really make a difference in the organizations and communities we are part of we must each continue to listen, to learn, and to show up with intention every day.

What are your experiences of becoming a more inclusive leader? Join the conversation in the comments or in the People Managing People Community, a supportive network of HR and business leaders building organizations of the future.

Some further resources to help you build more inclusive workplaces: