To say that political rhetoric has been intensifying since 2016 would be a gross understatement. It is everywhere, from your social media feed to holiday dinners and even the workplace.

Recently, one of the targets of that rhetoric has been corporate diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) efforts that have sought to level the playing field for underrepresented and marginalized communities.

In June, the Supreme Court’s decision to ban race-conscious admissions by higher education institutions increased speculation that corporate diversity programs will come next.

It took less than a week for the first lawsuit attacking DEI to make its way into the courts, with a group calling itself the “American Alliance for Equal Rights” filing a suit against two U.S.-based law offices for their diversity fellowships.

Many experts feel it’s just the beginning, as conservative political groups look to take advantage of a Supreme Court that leans in their favor. Their argument, in a nutshell, is that DEI efforts amount to discrimination.

“DEI is going through a beating right now between the Supreme Court’s decision and what’s going on in Florida,” says DEI consultant and executive coach Darrell Andrews. “A lot of folks are discouraged. A lot of companies are defunding it. Between the politics and perceptions of DEI that have been formed over the last couple of years, I would say it’s not over for DEI, but it’s definitely challenging right now.”

History Of DEI

Before we look at the future, it’s important to look back and see how DEI as we know it today has taken shape.

Following an era of landmark legislation during the 1960s, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and other anti-discrimination laws, what we know as diversity, equity and inclusion began as efforts to drive tolerance.

It was informed by Affirmative Action policies and wanted to further the aims that Affirmative Action had set out to achieve. Schools, workplaces, and whole communities were integrating and that period of change came with its own growing pains.

The period from the 1970s - 1990s is sometimes referred to as the Multiculturalism and Awareness era. Focused mostly on cultivating recognition, respect, and sometimes celebration for marginalized people, the goal was to prepare people for demographic changes as communities of color experienced greater social mobility.

This era is also defined by companies beginning to cast wider recruiting nets in an attempt to attract a larger talent pool, but in terms of diversity hiring, it was still done with a heavy focus on compliance with equal employment opportunity standards.

In the 1990s, the expectation that corporations mirror the demographics of the nation’s population through personnel began to take hold. A few people of color here, a female manager there simply wasn’t going to be enough anymore.

This was beginning to be backed up by academic research, which yielded insights on inclusion, turnover rates among diverse employees, and emotional intelligence as a key aspect of inclusive culture.

By the 2010s, equity and inclusion are introduced to the mix at most major companies. They are distinct concepts, but related in that they are driving toward the same goal. It’s around this time that the “business case” for DEI was made with regularity, using research from the previous two decades that showed the impact diverse teams had on innovation and the bottom line.

The narrative that diverse teams make better decisions and provide a wider variety of perspectives that benefit the business’ ability to innovate and reach new communities spoke to those at the highest levels of the organization. CEO Action groups formed, taking DEI from being the “right thing to do” to a business imperative.

Ebbs and Flows of the 2020s

As the clock struck midnight on January 1, 2020, no one knew what would lay ahead for the first year of a new decade, but things had certainly changed for DEI.

Budgets and initiatives were on the chopping block having faded from the list of priorities. A lot of companies were rolling back their efforts and questioning the business case more regularly. In a few months time, the need to be savvy with budgets was amplified as the coronavirus spread and the workforce and the economy were headed for uncertain times.

Then in May, as George Floyd was murdered in front of the eyes of the entire world, suddenly things changed.

DEI wasn’t just back on the table, it was a key business function to operate in a world where holding companies accountable for their pledges on social issues was conducted on both social and traditional media.

Seemingly overnight, citizens demanding social change also demanded that the brands who operate in the markets they spend their money in do more to further racial justice efforts. It didn’t matter if it was a bank, a clothing company, restaurant chain or the biggest names in tech, the expectation was the same.

Further resource: How to Set DEI Goals and Measure Your Progress

As a result, hiring for Chief Diversity Officers skyrocketed. Diversity as a function grew beyond HR to form its own teams and infrastructure. The focus of these teams went beyond the walls of the company, branching out into the community, small businesses, and social programs. Eventually, environmental, social and governance (ESG) strategies became key to garnering investment.

This sort of on again, off again enthusiasm for DEI tells its own story. It’s likely that demand for social change heats up again in the future, at which time corporations will once again come into focus as they wield a tremendous amount of influence over the nation’s workforce and overall culture.

“If we pull back the layers, it’s cyclical like the real estate market,” says Andrea Grant, a Human Capital Consultant with FutureSense. “Look at the “she-cession” that happened during Covid and how many women left the workforce and how many are now coming back to it now. Things go in ebbs and flows and DEI isn’t immune to it.”

Post Affirmative Action Ruling

At the moment, the perception is that things seem to be ebbing pretty hard. The fuel for that perception comes from the Supreme Court ruling and attacks on DEI in states like Florida, where funding for DEI efforts in public universities and state agencies has been prohibited.

Almost immediately following the court’s ruling, the idea that this could spread to cover DEI efforts in the workplace took off. But the notion that the entire discipline of diversity, equity and inclusion can be eliminated is far-fetched.

For one thing, a lot more has come out of DEI efforts than hiring policy. To paint it in a light in which the work of DEI comes down to showing favoritism to certain groups is reductive in the extreme and ignores policies and initiatives that have helped members of historically dominant groups as well.

Initiatives to eliminate or mitigate unconscious bias, for example, are a direct result of DEI efforts and are in tune with the court’s stance of what some are calling colorblindness.

Practices such as consistent interview questions for job candidates, collaborative hiring and refining promotion processes to make them transparent and merit-based aren’t going anywhere. In fact, they support the idea of meritocracy, something those arguing against DEI often champion.

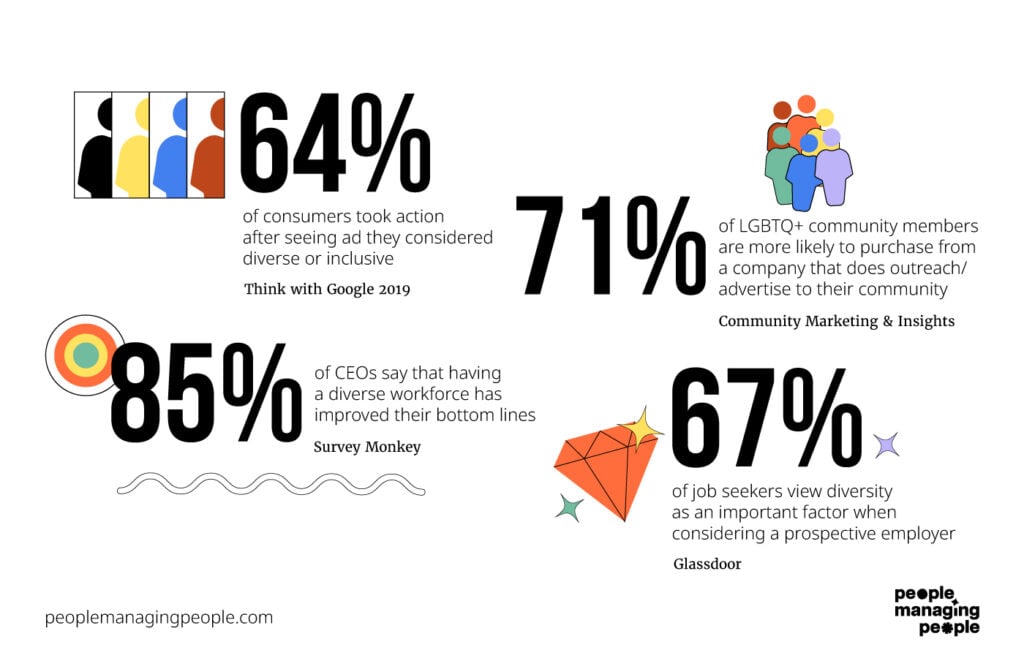

Grant believes that companies who sell DEI short now or walk away from it will ultimately pay a harsh price.

“They will absolutely pay a premium price in the long-term talent market and overall market,” she says. “My experience after over 20 years in HR tells me this but don’t take my word for it, look at the statistics.”

Some notable stats that Grant refers to:

- 64% of consumers took action after seeing ads they considered diverse or inclusive (Think with Google 2019)

- 71% of LGBTQ+ community members are more likely to purchase from a company that does outreach/advertise to their community (Community Marketing & Insights)

- 85% of CEOs say that having a diverse workforce has improved their bottom lines (Survey Monkey)

- 67% of job seekers view diversity as an important factor when considering a prospective employer.” (Glassdoor)

Misunderstanding DEI

Much of the work DEI does is in the background. Things like the creation of employee resource groups, mentoring and sponsorship programs, and promoting allyship are all examples of DEI work that isn’t specific to race or gender, but includes abilities, religion, sexual orientation and other intersections of human identity.

According to Grant, the narrow definition of DEI in the U.S. is part of the challenge it faces.

“DEI has historically been seen in the U.S. as race and gender only,” Grant says. “It’s a full spectrum of human experiences. Whether you’re looking at this through the HR lens or a strategic business lens, you do the same thing. You look at your workforce planning, you look at where you’re getting your talent from and how you are developing them. These are DEI issues.”

Further resource: 10 Best Diversity Recruiting Software for DEI Hiring

When companies look at their employer branding efforts, Grant’s point rings true. If a company has mostly men going through high potential programs, does no outreach to marginalized communities or isn’t offering learning and development opportunities for different learning styles that account for neurodiversity, that creates a message about the employer brand for the people who work there.

Hiring and promotion quotas for marginalized groups and using age, race or gender as a tiebreaker are practices that could come under fire as a result of legal challenges, but in some ways any decision the court could make on that is too late.

A lot of organizations and most DEI advocates left those ideas in the rearview some time ago as quotas became a way to do nothing more than check a box and do the bare minimum. In addition, neither quotas or the tiebreaker policy translated to a feeling of inclusion or belonging when those hires found themselves in meetings and break rooms.

“If we look for quotas, that’s when we get caught up ticking boxes and creating resentment from people in the workplace,” Judith Germain, Leadership Consultant at The Maverick Paradox said on a recent episode of the People Managing People podcast. “You do need to set some sort of goals and know where you started and where you want to be. But you also need to think about what a third party view would be. You want to get the best person and performance possible, so you need to make any changes in a way that honors the values of the organization, not one rooted in appearances or ticking a box.”

Perceptions Of DEI

Aside from politics, you may be wondering where all the vitriol for DEI is coming from.

According to Andrews, some of it has roots in what happened after George Floyd and the way DEI was delivered.

Andrews shared a story of a corporate client who called him in a state of emergency after hiring a diversity trainer. The trainer brought politics into the discussion from the start, discussing topics such as Blue Lives Matter and being adversarial toward people on the opposite side of the political spectrum. It poisoned the well for what could have been powerful work.

“At that time, DEI had a lot of momentum as corporations opened up whole diversity offices and executives were on board,” Andrews said. “It was a great opportunity to put systems in place, but when that window was open, some took it as an opportunity to come in and share their perspectives and thoughts or feelings on diversity, bias, microaggressions, and racism.

“The majority of people who were in these trainings didn’t meet it with resistance, but they did feel like ‘I’m not one of the people these folks are talking about.’ And I think that frustration you’re seeing now toward DEI is a byproduct of using it as a platform to vent frustrations and make people feel guilty. When people become offended, that doesn’t help anything.”

Another problem many DEI efforts have faced is among the primary cohort these policies are intended to benefit; employees.

Gallup researchers writing in the Harvard Business Review noted that only 31% of employees say their organization is committed to improving racial equality in their workplace. The same survey revealed a disconnect between HR and employees, noting that 97% of HR leaders feel their organization has made changes that improved DEI, but only 37% of employees agree.

Now, as the politics around DEI comes into focus, layoffs and budget cuts impact DEI departments and the whole function gets rolled up under HR or another department, employee perceptions are likely going to continue to shift.

“The momentum is swinging in this direction and this is who we’re becoming,” Andrews said. “I’m at an HR conference right now and we’re talking about the questions people are asking. Questions about what the culture is like, are there going to be growth opportunities? The fallout long term is going to be significant.”

A Shifting Landscape

For those in DEI, the structure of the teams they work on has changed a lot in recent years and it’s only going to keep changing. The last year has seen DEI positions cut with regularity, and nowhere more so than tech.

People who moved into DEI believing they were going to make a difference are, in many cases, looking for work or moving back toward other people operations positions like talent acquisition or HR.

Some companies have used the economy as a reason to cut back on both DEI and HR roles. But in Andrews’ opinion, the landscape is shifting based on how companies experienced DEI.

“The ones who had a great experience and saw the recruitment and retention benefits, you don’t see them eliminating the department, they’re sticking with it,” he says. “The ones where it was acrimonious, there was conflict in the way people were interacting and they didn’t really understand it, they’re either defunding departments or rolling it back up under HR. They’re looking to put some policy in place and try to make it work with fewer resources. The problem is that HR is having their own challenges from cutbacks in a lot of cases, so how are they supposed to take this on?”

Where DEI sits in the organization is not a new conversation and it’s one Grant doesn’t expect to go away any time soon.

“There’s been a lot of debate if diversity should live under HR over the years and I think it will continue,” she said. “I think it will continue to roll up under some other department or leader until the next big incident happens. Then they’ll invest in it again and then eventually they’ll collapse it again. Historically, that’s how it’s gone.”

There’s another issue at play. It has long been said that the success or failure of DEI rests with leadership. It’s why leadership accountability is a DEI metric measured by any respectable assessment of DEI commitment. But what happens when leadership turnover is high?

According to Russell Reynolds Associates’ Global CEO Turnover Index, turnover among CEOs was at an all-time high following Q1 of this year. Combine that with the turmoil HR and DEI teams have experienced and you begin to see how new leaders might be hesitant to support the policies their predecessors did.

“If leadership understands that this is a culture thing and they’re invested in it, that shows,” Andrews said. “But I have seen leadership that is split on it and they’re at war about it, and in some cases, that might be motivated by people’s politics. Leadership is really what drives this and determines the success of DEI.”

What Comes Next?

Right now, it’s hard for many in the DEI space to look down the road. Some organizations are being called out in various forms of media and people in the DEI space are losing jobs at an alarming rate.

“People are fearful because it has become so politicized, but if you really look, most businesses are doing something on DEI, they just may not be bringing attention to it,” Grant said. “I’m not in the business of changing hearts and minds. I’m in the business of changing behaviors and outcomes that tie to business.”

A good example of what Grant is referring to comes in the form of supplier diversity programs. Finding a wider range of suppliers for goods and services the business needs to operate not only opens up new opportunities for minority and women-owned businesses, it has the potential to save the business money as it shops for those goods and services in a more competitive marketplace.

It’s another example of why DEI work isn’t necessarily going anywhere, but what it’s called may change. Historically, DEI has been called different things and, in fact, it’s called different things now. Some organizations include the term belonging (DEIB), while others forgo the equity piece and simply say D&I. Others start with inclusion while some even advocate for a complete change of terms.

It’s been two years since the World Economic Forum declared DEI a failure and proposed changing the terminology to Belonging, Dignity and Justice. But if you think diversity, equity and inclusion has become loaded with political rhetoric, just wait until pundits and politicians are riffing on the use of the word justice in the workplace.

Belonging and dignity may have potential as these are universal concepts that apply to all groups equally and are easy enough to not only understand, but get behind. But whatever it’s called, Grant believes the work will not stop and the people who have been doing DEI work will continue to do so.

“The people who are doing this work are, in a lot of cases, doing it because of personal reasons and lived experiences,” Grant said. “They may not be doing it under the title of Chief Diversity Officer in the future, but there are different ways in which they will continue to do the work without the budget, the team and the platform they’ve had to talk about doing that work.”

How To Lead On DEI Right Now

For people leaders wanting to approach DEI in the right way, the question is what is the right way right now?

Andrews has always been a proponent of a humanistic approach, one focused on culture and relationship building. It’s vital not only in creating cultural conversations around DEI, but when approaching leadership about DEI as well.

“How do you make DEI inclusive from a conversation standpoint?” Andrews asks. “We’re all people, so you have to think about what’s the best way to approach that interaction so that they want to have a conversation. Those who come at it with a human touch and think about the best way to interact with people they want to have buy-in for DEI, they're more successful. We’ve seen a lot of people be open to conversation that normally would not. Those who come at it with politics find acrimony.”

As for supporting employees that DEI has sought to benefit, there is still work to be done to ensure their experience is on par with their peers. Germain thinks the focus needs to be on defining culture.

“For years, people have defined culture as ‘what we do around here,’” Germain said. “It’s also ‘who are we around here?’ We need to focus on a culture of belonging and having an environment where many voices get to speak in decision making. Diversity is often really diverse at the bottom of the hierarchy and the higher up you get, the less diverse it is. That means decisions get made by people who are not listening to diverse perspectives.”

To do that, Germain recommends two actions leaders can take any time. First, lead by example. Leaders should take a moment to ask themselves the following questions.

- What are the conversations that I’m supporting?

- What am I demonstrating to others?

- Do I have a clear set of values that people can see in my actions? If not, consider seeking guidance from a DEI consultant!

- Do the policies and practices of the organization support these values?

“I’ve seen it where people have a great vision for diversity, but when they do performance reviews, there’s nothing in the objectives that has anything to do with diversity in it,” Germain said. "Therefore, it becomes something that leaders don’t feel is important, so they don’t prioritize it. You’re actively taking money off the bottom line when you don’t do that. If it’s important to increase profits by 5%, then let’s not increase turnover and absence rates by objectifying people.”

There are also numerous DEI courses out there that can help you create a more inclusive workplace too.

To keep with the latest trends, news and ideas for people leaders, subscribe to our newsletter!