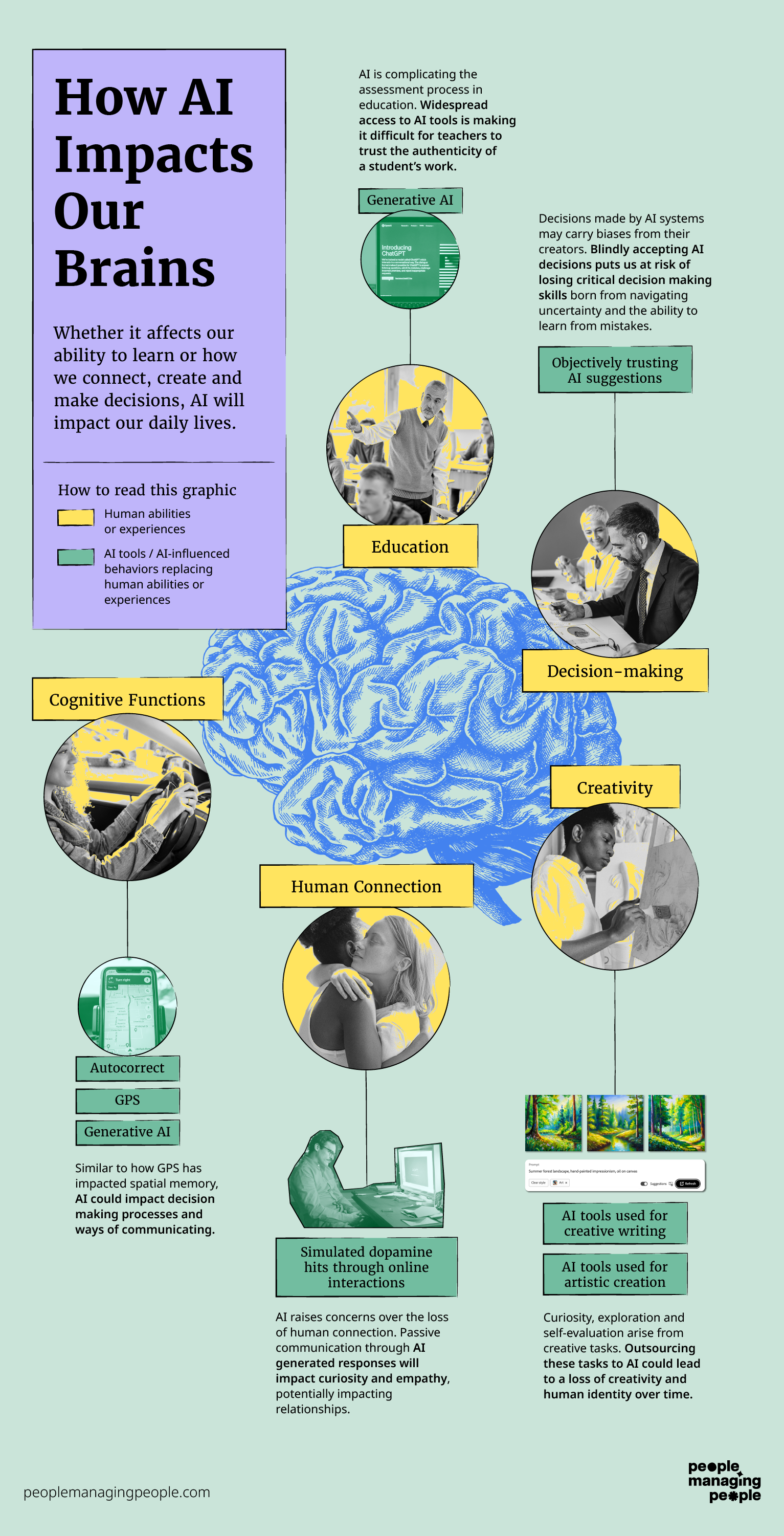

A study conducted by researchers at McGill University in April of 2020 found that the more a person used GPS, the steeper the decline in their hippocampal-dependent spatial memory.

What does that mean?

Basically, spatial memory, or your ability to remember where things are located, takes place in the hippocampus, a region of the brain heavily involved in memory, learning and emotion. It takes short term memories and transfers them into long term storage in our brains.

Over many centuries, human beings evolved to wayfind. It was an important skill in not only navigating your environment, but surviving in the days before cars, trains and airplanes. But as our societies have developed, there is less need for someone to polish such a skill and, in turn, less need to use this important brain structure.

This is not a phenomena limited to GPS. Few people remember phone numbers since cell phones acquired the ability to store a library of contacts.

Many people use autocorrect to fix the spelling issues within their texts and emails, no need to be a grammarian anymore.

But these tools are only effectively used when a human engages with them enough to get what they need from it. GPS can help you search locations, but you can’t find a person’s house without an address or at least knowing the area you’re looking at.

Likewise, your library of phone numbers is just information storage until you make a decision to press a button and call someone.

Even ChatGPT, which has caused quite the stir in the last year, requires your engagement. If you want to get something out of it, you have to prompt it.

For all the fuss about generative AI, it is largely, according to workplace futurist Alexandra Levit, author of "Humanity Works: Merging Technologies and People for the Workforce of the Future”, the most sophisticated chatbot we’ve seen to date.

Podcast: How to Use AI to Empower Your Employees & Transform Your Org

“If you dig into it, generative AI is not significantly different from what came before it,” she says. “It's a glorified chatbot and you still can't really trust the information you get.”

But trusting it we are. Content heavily influenced by ChatGPT is already being scattered across the internet. It’s being used to write emails, influence search engine optimization and analyze data.

All of this is relatively innocuous, at least on the surface. The question is, will long term use of this technology impact the user’s brain?

“I don’t think it’s really going to affect the human mind, except for how we search for and communicate information,” Levit said. “We've gotten progressively better at that using machines over the past 25-30 years and now people don't really know how to get information in a systematic way because you just type anything into Google, which is a form of AI.”

While generative AI is more or less a tool, it is an extremely sophisticated one that changes the playing field in many occupations. Someone who understands how and when to use it can change their entire workflow and in some cases even their skillset.

It’s for this reason you’ll hear people, including Levit, say with great frequency “AI isn’t going to steal anyone’s job, but a person who knows how to use AI will.”

This is true of this phase of AI’s development. For all Chat GPT’s strengths, it’s still a machine that more often than not provides a starting point for a human to create something meaningful or useful from it.

But the question remains, what happens as we challenge our brains less and less by welcoming automation? The common retort among AI evangelists is that we won’t be challenging them less, but differently.

By freeing up time currently spent on analytical tasks or something as arduous as writing a coherent thought ourselves, it will allow us to prioritize other things that only humans can do. Or so the narrative goes.

What exactly those things are that humans do better, however, is an area becoming less clear as AI technology advances at an incredible pace.

Even with AI providing the starting point to a project, it has an impact as AI is then playing a role in steering the work of humans. Humans who are already heavily distracted, navigating multiple screens and retaining less information than ever before.

How qualified or focused we are to determine whether what AI is giving us is any good is worthy of concern.

Stefan Ivantu is a consulting psychiatrist focused on adult ADHD in London. He’s quick to point out that in one respect, the brain is like any other muscle. If it isn’t used, it is liable to atrophy and we simply don’t know what the long term consequences of that happening from human interactions with AI might be.

What we do know is that the brain and our behaviors will change courtesy of new technology, particularly the ability to focus. All you have to do is look at history.

“If we think about the brain like any computer, it has two components, the hardware and the software,” Ivantu said. “So the hardware has been more or less the same for the past 200,000 years. But in the last century the software has been increasing exponentially. We didn't have access to electricity 150 years ago, which was a huge change in our day to day lives. From the 1950s when we first had access to the TV, the more we advanced, the screen came closer to our eyes. The computer, the mobile phone, now VR. The next one is the neuralink. The more we advance, the closer the screen comes to us. So now the question is, what is the normal level of distraction for us?”

Screen addiction has already caused shortened attention spans. I write this fully aware of the fact that you’re likely not reading it thoroughly, but scanning. Thus the shortened paragraph structure and attempts at well timed page breaks.

The fact is, technology has already been impacting our brains in ways we can see every day. Those developments aren’t likely to improve with increased use of AI and the instant gratification that it provides for everything from writing a report to providing the foundation of a recruiting strategy.

AI-powered recruiting systems can even change the way we engage with recruitment, affecting how our brains process candidate data.

“All of these technologies allow us to be lazier and to not use parts of our brain that are intended for use,” Levit said. “They're already atrophying. I think when it comes to evolution, it's going to be a long time before we have evolved to not perform a given function, but we see across the board with technology that people are more distracted, they can't focus. They're less productive already because of app fatigue. They're mindlessly switching from one thing to another, but they're never really focusing on any one thing. Even if we want to focus, a lot of times we can't.”

The Next Phase

Bletchley Park was an ideal scene for the first AI summit of state leaders worried about AI’s potential to drive industrial and social change. It was there that the world’s first programmable digital electronic computer was built as the allies attempted to understand German codes for communications during World War II.

We’ve come a long way from that revolutionary moment in computer science, a discipline that may now hold the fate of humanity in its hands courtesy of AI’s potential.

Plunge down the research rabbit hole on AI and it won’t be long before you get to what the next phase is, interactive AI.

Companies like DeepMind are inching ever closer to interactive AI as a reality, one where bots carry out tasks that humans set for them simply by calling on other software or people to get things done.

Sounds nice enough, but how long each phase of AI will last at the rate it’s developing is a source of uncertainty.

Go any further down that rabbit hole and you’ll come to AGI, or artificial general intelligence, a system capable of accomplishing intellectual tasks that humans and animals perform.

It is no longer the stuff of science fiction, but the goal of companies like OpenAI, DeepMind, Microsoft, Google Brain, IBM and others with tremendous financial resources at their disposal that are pushing us toward AGI being a reality at an alarming rate.

“With AI, the danger is kind of an existential thing,” Levit said. “When we do achieve artificial general intelligence, which means that machines are essentially conscious and they can think better than we can, is there any need for us to do anything anymore? Like what will be our purpose? I don't think we'll evolve to not do anything but we might just practice doing things. With AI, I would be most concerned with the fact that it's going to render us obsolete, because it'll just be better at most things.”

More people in power are waking up to this realization. For that reason, President Biden signed an executive order to establish standards for AI safety and security.

The 29 countries which met at the first AI Safety Summit agreed on an agenda that will focus on safety risks of shared concern, the creation of risk based policies and a global approach to understanding AI’s impact on society.

The Developing Mind

There are two main areas in which Kentaro Toyama, computer scientist and professor of Community Information at the University of Michigan’s School of Information, warns AI could have a significant impact on the human brain. The first is education.

Like a lot of things with AI and life, you can find a balance of good and bad in it if you look at it objectively.

Podcast: How AI Can Support You Being a Great Manager

In theory, AI could provide students with tailored, personally customized forms of instruction that are more engaging and help learners absorb information more thoroughly. The same can be said for workforce training.

At the same time, Toyama sees the potential for a reality where AI makes educating remarkably difficult and, in fact, already is.

“If everybody has access to it, it becomes harder and harder for teachers to do their job,” he said. “Right now, any kind of faculty is in a situation in which we can no longer say with certainty whether something that a student hands in was done by the student. I have colleagues that have had to revamp the entire way they do assessment because that's the underlying issue.”

While the former Microsoft researcher emphasizes that there is nothing fundamentally wrong with incorporating technology into learning, he’s quick to point out that if it clouds the assessment process, then the methods and practices of teaching are not going to be very effective.

“You can’t teach unless you know what the student knows and what they don't know,” Toyama said. “My prediction is that people who are serious will go back to blue books and proctored exams, where people are writing things out by hand.”

The Value Of Human Relationships

If you listen or talk to AI experts and people close to its development long enough, you’ll get a sense that there is a belief that in the future, human connections will become incredibly valuable.

Our relationships with other people are an important part of our mental health and a defining element of what makes the human experience what it is, whether it’s at work, school, church or the grocery store.

“Look at the pandemic,” Levit said. “It was like a collective trauma that everyone was isolated for so long. It really messes with people's heads. I think that we are in danger of continuing that and with the screen addiction of kids, this up and coming generation are on screen all the time, most of the time in lieu of real social interaction. It'll continue to be difficult to facilitate that human interaction that used to happen just naturally in every environment. It’s going to become more valuable because it'll be harder and rarer.”

Fundamentally, part of this belief is based on the fact that there is no replacement for human interaction. That dopamine hit that comes from a successful or pleasant social scenario is one of those things most of us know and enjoy. But is it truly irreplaceable?

Research has shown that online interactions in which two people never actually speak can deliver a dopamine hit for the brain. Even someone just liking your LinkedIn post has this effect. The caveat to why that is, of course, is that you are under the assumption that the person on the other end is a real flesh and blood human being, whether you know they are or not.

Research on our brains as we interact with AI is as much in its infancy as the technology, if not more. But you don’t have to be a scientist to understand that the belief that it’s possible for AI to satisfy our need for connection exists.

Just look at films like Her or certain episodes of Black Mirror or literary works like Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun.

“It’s a big unknown,” says Toyama. “Will we find sufficient connection with knowing that something is a machine? Will we feel fulfilled and satisfied in a relationship with a machine to the point that we stop seeking actual human connection? It's not clear.”

Toyama gives the example of MIT researcher Joseph Weizenbaum, who became one of AI’s biggest critics in his later years.

In 1964, Weizenbaum created ELIZA, an early natural language processing program designed to use pattern matching and substitution methodology to create an illusion that the program could understand humans.

It ran a script called DOCTOR, which created a conversation similar to what a therapist might have with a patient. Essentially, ELIZA could repeat things that you said and ask you more questions about it. It was, for all intents and purposes, an early chat bot.

To Weizenbaum’s surprise, users became convinced of ELIZA’s intelligence and understanding. Some began to attribute human-like feelings to the program and people began to use the technology seriously, seeking a therapeutic interaction.

“That was in the 60s,” Toyama said. “These days, there's already companies that are suggesting that they can, for example, handle some part of the texting interaction with your mother. That's already beginning to happen. So again, it's not clear how people will respond to technology. I can foresee ways in which there could be good things that come out of this, but a lot of it is a little bit frightening, at least from the perspective of valuing human relationships.”

So maybe today, you’re still talking to mom personally and you think that example is far fetched. But I’ll bet you already use AI to communicate to other people. You may have even had an AI conversation with someone using prompted responses.

A good example of this is automated response options in emails or text. You receive an email that requires a simple response and there the options are below the text field in your email saying things like “Sounds good” or “Awesome! Thanks.” In some cases, perhaps it’s a follow up question such as “What time?”

The options are simple, but in order for them to suit the context of the conversation, the engine prompting you with those options has to understand what response would make sense in that situation.

Given how quickly things are developing, Toyama can see another scenario coming together that might not be all that great for business.

“Within a few years, if not months, we're gonna start seeing the whole email drafted for us. Once that starts happening, many of us won't even read that email or the response. Then something is going to happen, there's gonna be situations where neither side is really paying attention to automated machine responses to each other. We'll have relationships that are based on communications that we didn't really pay attention to and there will be mistakes. If the mistakes are severe enough, we'll start paying more attention but a lot of relationships will happen on snooze.”

This sort of passive communication has risks for the brain in that, with depth comes curiosity and interest.

Empathy, an important stimulator of brain activity, is driven by a desire to understand fellow human beings. If that desire isn’t there or is supplanted by technology, human beings run the risk of losing something bigger than clarity of communication.

“One area I can see issues is around curiosity,” Ivantu said. “People will become less and less curious about each other and would rather look for right or wrong. Don't be surprised if there are going to be tools out there which will say they can read someone's emotions. It's going to be less and less discovery, less curiosity, and curiosity is what drives humanity in the first place.”

The Expression Of The Brain

can we get some a.i. to pick plastic out of the ocean or do all the robots need to be screenwriters?

— Matt Somerstein (@MPSomerstein) May 18, 2023

The above Tweet highlights an important issue with the case for AI. In years gone by, proponents of the technology would often say things like “AI is going to do all the jobs humans don’t want to do.”

Under the assumption that AI would be working in meat packing plants and diving into coal mines, a lot of people began looking forward to a future with AI. Instead, it arrived with the ability to craft short stories and scripts for commercials.

An essential element of being human is our ability to express ourselves. This is why in dystopian fiction, a common thread is the breakdown in people’s ability to communicate or understand each other, be it the stupidity on display in a film like Idiocracy or the misfortune in something like The Silent History by Eli Horowitz.

Human expression and creativity go hand in hand. Creative tasks often lead us toward finding new ideas, ways to communicate them and new approaches to solving problems. They ask us to think about consequences, different points of view and force us into self evaluation.

The curiosity and exploration that comes along with those tasks is, according to Ivantu, at the center of our growth as human beings. While he is in favor of AI’s development in positive use cases, he warns that if AI increasingly removes those tasks from our cognitive plate, there may very well be a tangible cost to our brains over time.

“If this sort of skill is handed over to a machine, then ourselves as human beings, we're losing our identity,” he said. “AI should be a tool that helps the human and human behavior to achieve better results. Really simple tasks can be delegated, but I don't think it should be utilized as a tool that will replace everything else. Same as the cryptocurrency craze when people were worried during the pandemic and saying it’s going to replace all the money in the world. Does it have a place? Yes, but it is limited.”

As you might expect, there’s a world where AI helps humans with certain creative tasks without much cost to human expression, but it will ultimately come down to a human commitment to continuing to create without AI’s assistance.

“The hopeful example is chess,” Toyama said. “In 1997, Garry Kasparov lost to a computer (IBM’s Deep Blue) and the world has never gone back. Like at this point that computer chess in your pocket can beat the best chess players in the world. So you might say, what's the point of playing chess? But in fact, human interest in chess is still alive and well, there's still drama in it. And people who care about it still want to play. Hopefully that kind of spark is there within us as humanity and the things that we value about creativity won't go away.”

The Loss Of Valuable Human Skills

Let’s be clear about something. There are several positive use cases for AI, particularly in healthcare.

This isn’t a story attempting to peddle fear about AI. How it’s used and what for is entirely up to human beings. At least for now.

But we are at a critical moment that will shape our future over the coming decades and beyond and in that long term, it will impact our brains in some way.

The problem that has experts from Levit to Geoffrey Hinton, often called the “Godfather of AI”, and a whole host of other AI researchers and developers now ringing the alarm bell is that much of what has taken place hasn’t happened within the public eye or with any oversight.

“I'm always banging the drum of human oversight,” Levit said. “We’re at the point where it's capable of making decisions but how? You have to understand the data that it has at its disposal to come up with those conclusions. You have to be able to detect bias because AIs are only as unbiased as the people who create them. You really have to be vigilant about how you ingest accepting a decision because the AI says so. Blind acceptance is the exact wrong thing to be doing and that's what's happening. A lot of workplaces are empowering AI to make decisions for people.”

Levit’s warnings of taking AI decision making at face value under the assumption they’re more objective ring true with the warnings of experts like Hinton.

Recently, a large number of concerned AI engineers and experts endorsed a consensus paper which outlined some of the biggest risks.

Among the concerns:

“To advance undesirable goals, future autonomous AI systems could use undesirable strategies—learned from humans or developed independently—as a means to an end. AI systems could gain human trust, acquire financial resources, influence key decision-makers and form coalitions with human actors and other AI systems.

To avoid human intervention, they could copy their algorithms across global server networks like computer worms. AI assistants are already co-writing a large share of computer code worldwide and future AI systems could insert and then exploit security vulnerabilities to control the computer systems behind our communication, media, banking, supply-chains, militaries and governments.”

Putting all of the terrifying possibilities aside, let’s just focus on one part of that segment from the paper. “AI systems could gain human trust and influence key decision makers.”

In terms of the business world, it’s not a matter of “could”. It already has. And it’s playing out in strange ways.

The first robotic CEO made its debut recently. Sure, for now, it’s a Polish rum company most likely looking for a publicity stunt, but everything starts somewhere. Even if it's a joke, there’s bound to be someone who simply doesn’t get it.

In a video released by the rum manufacturer, Dictador, the robot, named Mika, looks into the camera and says: "With advanced artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, I can swiftly and accurately make data-driven decisions."

Her style of clothing and ethnically ambiguous features are intentional efforts by manufacturer Hanson Robotics to make Mika feel human to as many people as possible, a key factor in gaining the trust of human beings.

Hanson Robotics CEO David Hanson has publicly emphasized his belief that “humanizing AI is a critical step in ensuring the landscape’s safety and effectiveness as humans and robots continue to collaborate in the future.”

As AI takes over more decision making power, it will relieve pressure from human beings without doubt, but it’s that same pressure which has caused us to learn, adapt and grow our capabilities faster than all the other creatures on the planet to this point.

“Let’s say you have to make a difficult decision at work and you don't know how it's going to play out. The uncertainty is the thing which is producing growth, innovation and discovery,” Ivantu said. “If you just accept a decision that something is either good or bad, you overlooked an opportunity that is out there. And I think that is the highest risk in utilizing AI, because the decision was made for you. You do not have the chance to explore and make mistakes, which is needed to find new life, new concepts and so on.”