Why is crisis management important?

At the time I'm writing this article, it's early April 2020. A crisis of pandemic proportions is ravaging the globe. The COVID-19 virus has killed tens of thousands and infected more than a million. Stock markets have fallen, world economies have been hit, and businesses large and small have been impacted, with many fighting just to survive.

In addition to the physical threat of the virus, people’s mental and emotional well-being is at risk. COVID-19 is a “crisis” in every sense of the word.

This article is intended for the Human Resources professional looking for guidance on how to manage through a crisis, whether it’s a pandemic like COVID-19 or a fire in your organization’s stock room.

We’ll cover a wide range of topics, from the basics of what crisis management is and why it’s important, to the different responsibilities of HR and the various stakeholders within the organization.

Much of this article will focus on the specific role of Human Resources, but anyone in a management or leadership position can benefit from understanding what’s involved in crisis management.

In fact, as we’ll explain later on, crisis management simply doesn’t work without the support and buy-in of everyone, whether you’re a senior executive like the CEO or a manager on the front lines.

- Key characteristics of a crisis

- Types of crises and disasters

- Basic elements of crisis management

- The typical crisis management process

- HR’s roles and responsibilities in crisis management

- Elements of an Effective Crisis Management Plan (CMP)

- Key success factors for effective crisis management

What are the key characteristics of a crisis?

So, what is a crisis? A crisis is anything that poses a serious threat to the health and future of a business’s operations, finances, reputation, and/or people. A crisis is typically:

- High impact

- Low probability

- Unexpected

- Unique

A crisis has the potential to highly impact a business. The definition of a “high” vs. “low” impact is often subjective. Some companies might view the possible loss of a key customer as having a high impact - and therefore be considered a crisis - while others might simply view it as part of doing business.

There’s usually a low probability of the crisis occurring, so when it does occur, it is often unexpected. In addition, a crisis might affect just a single business or an entire industry.

Boeing, for example, faced a major crisis in 2019 following two fatal plane crashes involving their new 737 MAX aircraft. Their management of, and response to, the crisis was often criticized, and it caused massive damage to their reputation, stock price, and financial strength. Even worse, the entire airline industry suffered. Carriers grounded planes and canceled flights, causing massive disruption not just to their own businesses, but to people traveling around the world.

A crisis typically comes without much, if any, warning. Also, because it is unique (every hurricane and computer virus is different), it doesn’t allow for detailed step-by-step planning in advance. Some felt that when Apple CEO Steve Jobs died that the company would be faced with a leadership crisis.

Whether it was a crisis or not is debatable, but because of the nature of his death (a long battle with cancer), Apple had enough time to create a succession plan that enabled Tim Cook to smoothly transition into the leadership role.

What are the types of crises that can occur?

In order to create a crisis management plan, the organization must identify some of the most likely crises that could affect the organization.

However, it’s impractical (and impossible) to anticipate and prepare for every possible crisis, so start with the ones that are most possible.

For example, if your company headquarters sits on an earthquake fault line, you should probably have a documented procedure for employees to follow in case an earthquake hits.

Similarly, if your organization is in Vancouver, Canada, you probably don’t need to prepare for a hurricane. That said, if one of your sole suppliers is based in Florida, it may be necessary to be prepared in the event of a disruption in supply.

When we talk about crisis management, a crisis doesn’t necessarily need to come from a global event like a pandemic. There are many different types of crises that can erupt, such as:

- Natural disasters (e.g. earthquakes, hurricanes)

- IT or network infrastructure outages (e.g. computer viruses, hardware failure)

- Damage to company property or infrastructure (e.g. fire, flood)

- Death or injury of key employees

- Violence or other attacks against employees

- Lawsuits or legal action.

The severity of a crisis, in terms of the potential impact on the business, is often relative. A broken pipe that leads to the flooding of a local grocery store, for example, would constitute a serious threat to that business.

The flooding of one of McDonald’s 37,000 restaurants, on the other hand, would be considered a crisis for that particular location, but probably not one for the larger McDonald’s organization.

Other crises, however, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, would likely be considered a serious threat to a huge number of businesses, large and small.

Is a crisis the same as a disaster or catastrophe?

A crisis isn’t the same as a disaster. Louisiana State University’s Stephenson Disaster Management Institute makes a clear and useful distinction between the two:

“We define a crisis in terms of a threat to core values or life-sustaining systems, which requires an urgent response under conditions of deep uncertainty. We define a disaster in terms of the outcome or consequences for society: a disaster is a “crisis with a bad ending.” When a crisis is perceived to have really bad consequences, we speak of a catastrophe.”

A crisis isn’t the same as a disaster, but a crisis can quickly become a disaster, and vice versa.

In 2016 a series of earthquakes, including a magnitude 7.0 mainshock, struck Kumamoto City in the Kyushu region of Japan.

The resulting damage to factories and businesses was a disaster in every sense of the word. The earthquake also led to a crisis for many businesses outside of the region that relied on products being manufactured in Kumamoto.

Sony’s image sensor manufacturing plant, for example, was one of the factories damaged by the earthquake. Camera companies around the world relied on this factory to build their own products and had to act quickly to manage the ensuing supply crisis.

What is crisis management?

Now that we understand more about what a crisis is, what is crisis management?

Crisis management is a system of plans and processes designed to enable an organization to detect and minimize the potential harm posed by a crisis and subsequently learn from crises that arise.

The ultimate goal of crisis management is to move the business back toward normal operations as efficiently as possible with minimum damage to the business.

Crisis management requires more than just a plan and the execution of that plan when something bad happens. Crisis management requires that your business be prepared to evolve, learn from, and change how they handle a crisis in response to whatever unique and extraordinary challenges that particular crisis presents. It’s impossible to create step-by-step plans on how to handle every possible crisis since every crisis will be unique and unfamiliar to those in the business.

Starbucks may have had crisis management plans in place in 2018. However, the company definitely did not have a plan on how to handle a racism crisis when two innocent men were arrested in one of their stores after a staff member called the police.

They had to quickly adapt to a unique and extraordinary crisis that could dramatically affect their reputation.

In that case, Starbucks took the extreme measure of closing all 8,000 of its stores across the United States to conduct racial-bias training. They estimate it cost the company over $12 million of profit, and whether the training was successful or not, it at least served to show the public that Starbucks was taking the matter seriously.

What does a typical crisis management process look like?

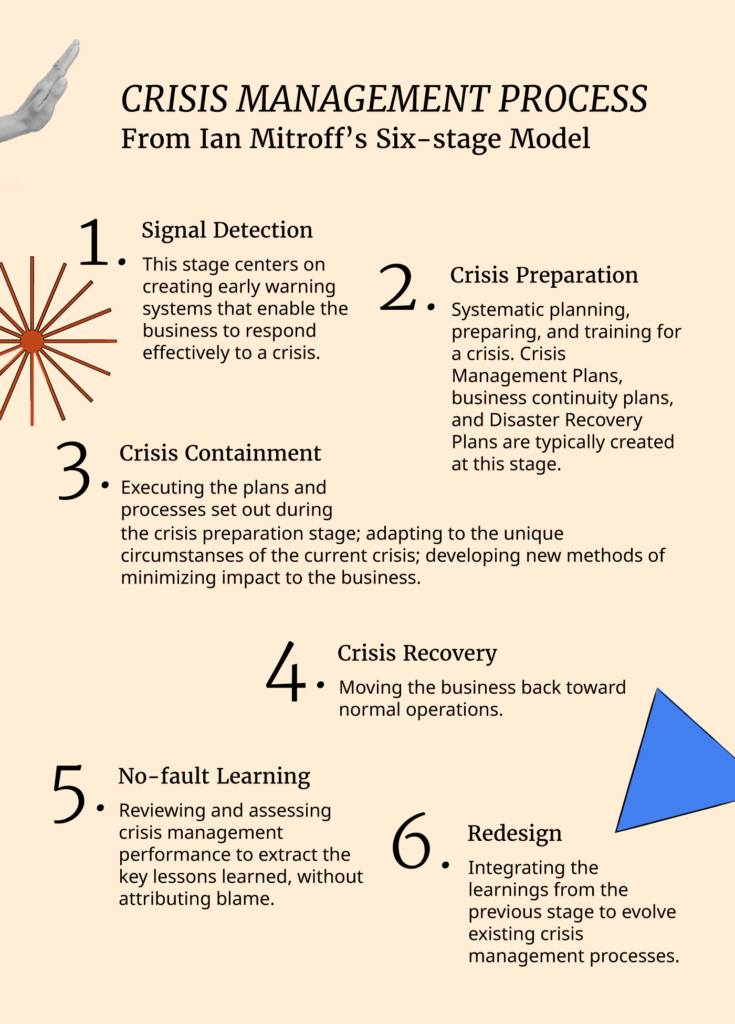

One of the most commonly referred to frameworks used to describe the crisis management process comes from Ian Mitroff.

Mitroff’s six-stage model is a useful reference for crisis managers, those in HR, and other stakeholders responsible for crisis management.

Here's a graphic of the model and there's a written explanation of each below:

- Signal detection: this stage centers on creating early warning systems that enable the business to respond effectively to a crisis.

- Crisis preparation: systematic planning, preparing, and training for a crisis. Crisis management plans (CMPs), business continuity plans, and disaster recovery plans (DRPs) are typically created at this stage.

- Crisis containment: executing the plans and processes set out during the crisis preparation stage; adapting to the unique circumstances of the current crisis; developing new methods of minimizing impact to the business.

- Crisis recovery: moving the business back toward normal operations.

- No-fault learning: reviewing and assessing crisis management performance to extract the key lessons learned, without attributing blame.

- Redesign: integrating the learnings from the previous stage to evolve existing crisis management processes.

Is crisis management different from change management?

Crisis management and change management share many similar practices, and a crisis is often the catalyst for broader organizational change.

In 2017 a number of negative reports about Uber’s workplace culture began to emerge in the media, including one from the New York Times.

Many of these reports centered on alleged discrimination against women and cases of sexual harassment.

This internal crisis was compounded by a number of other issues, which ultimately led to the departure of the company’s CEO.

Any change in an organization’s senior leadership, particularly when it’s the CEO, requires effective planning, communication, and adaptation.

Related Read: Build Resilience Using The 3 Rs Technique

Who is responsible for crisis management?

Dealing with crisis management is not the sole responsibility of Human Resources (HR).

Many organizations - typically larger ones - may have a dedicated “crisis manager” who oversees all aspects of crisis management planning and execution.

Organizations that don’t have the resources for a dedicated crisis manager will instead rely on someone to step into the crisis manager role when a crisis occurs. Who that person is maybe different depending on the nature of the crisis itself.

Regardless of who the crisis manager is, effective crisis management requires the cooperation and coordination of many stakeholders within the organization, including teams from HR, legal, IT, finance, operations, and public relations.

While all of these teams might be involved in crisis management, the extent of their involvement will vary depending on the nature of the actual crisis.

For example, in the case of a computer virus, the IT department might carry a higher burden of management than the PR department.

What is HR’s role in crisis management?

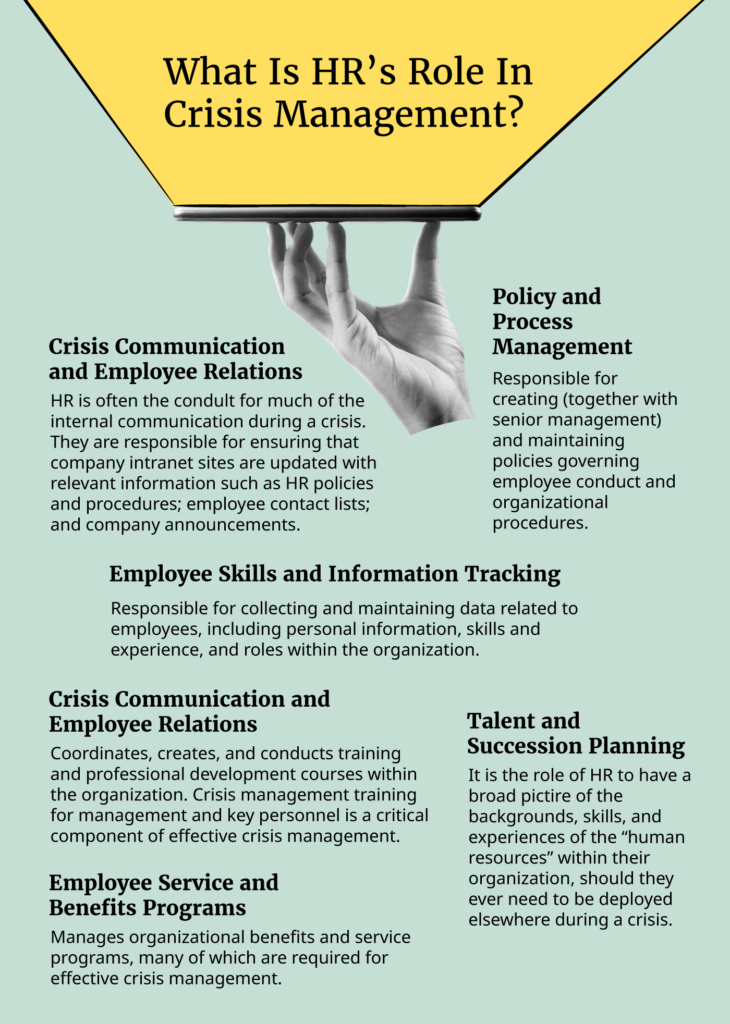

HR’s role in crisis management is broad and varied, and typically includes:

Crisis communication and employee relations

HR is often the conduit for much of the internal communication during a crisis. They're responsible for ensuring that company intranet sites are updated with relevant information such as HR policies and procedures; employee contact lists; and company announcements.

HR can also work with management and leadership to ensure that crisis communication is consistent across the organization, and that appropriate FAQs are developed to answer questions about the crisis.

HR can further provide employee feedback to management so that changes to crisis communication can be made.

Policy and process management

HR is typically responsible for creating (together with senior management) and maintaining policies governing employee conduct and organizational procedures.

This would include acting as the repository for the crisis management plans and procedures.

Every crisis is unique and unfamiliar, which often requires company policies to be rapidly created or modified. For example, COVID-19 required many to work from home.

HR can coordinate with departmental managers to create guidelines on who can / should work from home, and with IT to ensure the appropriate remote work systems are in place to enable it.

Employee skills and information tracking

HR is responsible for collecting and maintaining data related to employees, including personal information, skills and experience, and roles within the organization.

This data is often stored in a central repository such as a Human Resource Information System (HRIS). An HRIS allows easy access to information that could be useful during a crisis, such as which employees have first aid training, who to contact in case of an emergency, and employee counts by department or location.

Training and development

HR often coordinates, creates, and conducts training and professional development courses within the organization. Crisis management training for management and key personnel is a critical component of effective crisis management.

Training can include everything from fire drills to more in-depth leadership courses geared specifically toward crisis management.

Employee service and benefits programs

HR manages organizational benefits and service programs, many of which are required for effective crisis management. Employee Assistance Programs, for example, can be used to connect employees with mental health care providers.

Health benefits are necessary to help injured employees receive medical care, and to enable them to rehabilitate and recover quickly so that they may return to work.

Since the goal of crisis management is to return the business to normal operations as quickly as possible, it’s extremely important to have healthy employees capable of doing so.

Talent and succession planning

Some crises may lead to certain employees being unable to do their job. HR is typically responsible for succession planning and working with managers to identify the talents of the employees on their teams.

If a crisis has led to the serious injury of a team leader, for example, it’s important to know who - if anyone - can fill in for that team leader while they recover.

It's the role of HR to have a broad picture of the backgrounds, skills, and experiences of the “human resources” within their organization, should they ever need to be deployed elsewhere during a crisis.

I've summarized these points in a simple graphic below:

What does a good Crisis Management Plan (CMP) look like?

There is no universal template for an effective Crisis Management Plan (CMP). The CMP will be unique to every company and tailored to their size and needs.

A large multinational, for example, will have a very different CMP than that of a small business with a single location-based in Canada.

Similarly, a CMP for a company whose business is selling products to consumers (B2C) will look different from one selling to other businesses (B2B).

However, while the content of a CMP will vary between organizations, there are some common characteristics and elements that every CMP should have.

Crisis management team(s):

Your organization’s CMP should clearly outline the team(s) responsible for crisis management and the business and contact information for each member of the team.

Your organization may have a single crisis management team, or one “oversight” team and multiple sub-teams. These sub-teams may be defined in advance or assembled ad-hoc during the crisis itself.

Roles and responsibilities

Your core crisis management team should have senior leaders, and ideally executive members, to ensure that decisions can be made quickly and with authority.

The crisis management plan should briefly outline the roles and responsibilities of each individual, and identify special areas of expertise that may be useful during a crisis.

Crisis management procedures

Once you’ve identified the types of crisis you want to prepare for, you can begin to create the procedures that managers and employees will rely on to help return the business back to normal operations as efficiently as possible.

These procedures should not be overly long and detailed; they should communicate steps visually (e.g. infographics, diagrams) vs in writing, as much as possible; and should clearly describe what a “good” result looks like if the plans are executed correctly.

For example, you might have a procedure for a fire drill that graphically shows the proper escape routes and muster locations, with the goal of being able to account for every member of your team.

What are the keys to successful crisis management?

“Success” in crisis management can generally be defined as the resumption of normal business operations with a minimum of damage to the business. Effective crisis management doesn’t come from a handful of procedures kept in a binder in HR. A documented Crisis Management Plan that is coordinated and maintained by Human Resources is a necessary part of the equation, but successful crisis management requires a number of other key elements.

Effective leadership and executive buy-in

David Perl, Chief Executive Officer at Docleaf Crisis & Risk Management, writes that leadership “is perhaps the most critical success factor required” in managing a crisis.

He notes the importance of effective leadership in terms of ability to delegate; being calm under pressure; quick and effective decision-making; and being able to communicate.

Perl also mentions the requirement that effective leadership also means being empowered to spend money. In the Starbucks example mentioned earlier, for example, someone in a leadership position had to make the decision to close thousands of stores for the day, sacrificing millions of dollars in the process.

Strong crisis leaders will avoid knee-jerk reactions to cut costs and minimize expenses in the midst of a crisis.

A recent Newsweek article reported on a number of large companies that are continuing to pay their employees despite stores being closed.

These businesses understand that while not paying their employees might save money in the short-term, it is not an effective strategy for long-term recovery from the crisis.

It’s also not enough for HR and other stakeholders to make crisis management a priority. Effective crisis management, from the signal detection stage through to redesigning crisis management processes, requires the support and buy-in of the organization’s senior leadership.

Obtaining executive support and approvals to design and deploy crisis management plans is perhaps one of the most important factors in successful crisis management.

Speed and quality of communication

The speed and quality of crisis communication are one of the most important factors affecting the outcome of a crisis.

In a recent survey, Gallup gathered the strategies and policies of 100 members for their crisis responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. They found that “corporate leadership is communicating frequently -- daily, weekly or as available -- to address their organization's COVID-19 crisis response, advice, policies, and protocols.”

Gallup also found that leaders are tailoring their communication to different groups - employees, managers, customers, etc. - and using a variety of methods, such as email, social media, and video conferencing.

There are a number of distinct characteristics of effective communication during a crisis:

Quick response

Traditional crisis management refers to a “golden hour” of communication, which is the (often short) amount of time that a company has to respond to a crisis, explain the situation, assert the facts, and outline how it will respond.

In a recent article, Victoria Cross, Head of Instinctif Partners’ Business Resilience Practice, notes that “the growth of digital and social media has dramatically reduced the golden hour to little more than a few seconds,” requiring organizations to adapt and become even faster with their crisis response and communication.

Single points of contact

There will often be multiple people/teams managing communication during a crisis, but it should be clear who is responsible for what.

For example, HR is often the point of contact for employees internally, while Marketing / PR is usually the point of contact for the press and media. Sales may handle communication with customers, and operations may deal with vendors and suppliers.

These points of contact should be clear and well-documented in the crisis management plan.

Easily accessible

Communication about the crisis should be readily available to all impacted parties. Common platforms for crisis communication include company intranets; social media channels; direct emails; corporate websites; telephone hotlines; and internal signage.

Companies with operations, customers, and/or suppliers in other countries should also be prepared to make crisis communications available in other languages, with the content localized for other cultures and business methods.

Simple and flexible plans and processes

A crisis management plan is not a step-by-step “how-to” guide for every individual crisis. Your CMP should not be a 75-page document, double-sided, written in 8-point font.

No one will ever read it, and if / when a crisis does erupt, it will be extremely difficult to use. Crisis management requires simple, easy-to-follow procedures, and the ability to adapt these to the unique circumstances of a crisis.

It would have been hard for JC Penney to anticipate and plan for the PR crisis that erupted when they released a billboard advertisement for a tea kettle that bore a striking resemblance to Adolf Hitler.

When it did happen, however, they were quick to react and adapt to the unique situation by removing the billboard and responding on social media with honesty and humor.

What Do You Think?

Have you ever produced or used a crisis management plan? Does your organization have a crisis management procedure? Do you think it’s important, and if so, how will you (or did you) go about convincing senior management to support its development?

Weigh in on these questions in the comments below and subscribe to the People Managing People newsletter to stay up to date with the latest thinking in HR from leadership and management experts from around the world.

Some further resources to help you build more resilient organizations and navigate change: